Taking the Bucket Out of the Bucket List,

Part 1

by Karen S. Wiesner

In this two part article, I discuss the wisdom and benefits of, and strategies for, drawing up a personal bucket list as early as possible--long before the curtain of a life is drawn.

Thanks for my fellow blog mates Rowena and Margaret for inspiring this impromptu article with their suggestions for potential topics I could cover on Alien Romances. Also thanks to those who critiqued this article for their suggested improvements and enthusiasm before it was posted.

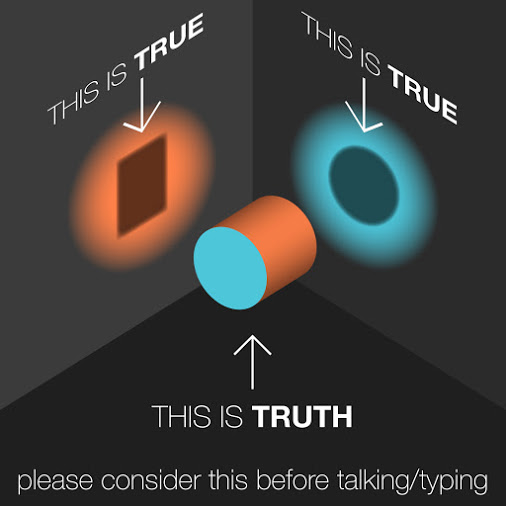

About 10 years ago, I sort of watched the movie The Bucket List out of my peripheral vision. My husband is fond of watching movies on one of our TVs while I play Xbox games on the other. Condensing the theme of that movie, two terminally ill, older men come up with a wish list of things they want to do--and, in an abbreviated amount of time, they attempt to fulfill them--before their time on Earth literally runs out. My first thought in response to the theme of this film was, Why would anyone want to do this when they're old, tired, dying, and it's nearly too late? Why not do the things you're passionate about long before there actually is a countdown to death and while young enough to truly enjoy the adventure(s) undertaken? Few questions have ever motivated me more than these two.

As far as the internet can tell, the term "bucket list" was either created or popularized by that 2007, so-named movie. A bucket list is believed to relate to the idiom "kick the bucket", which is a term that originated in the 16th century. Be prepared to cringe: The wooden frame that was used to suspend slaughtered animals was called a bucket. I think you can guess what happened after they were hung up by their hooves. Yikes. Long story short, there was a lot of kicking done just prior to death. A bucket list, then, is created to clarify what one wishes to accomplish either in a specific timeframe (as in, "one and done" tasks completed in a short amount of time) or by the end of a life (long-term projects). Bucket list wishes can be self-actualization goals or ones you've set for endeavors such as charity work, career, or family or friend-related purposes.

While at that time I didn't really sit down and write up a formal bucket list of my own, I thought long and hard about which goals would make mine. The most important factors in doing this, for me, were, first and foremost, that I would be able to enjoy them all throughout the rest of my life, and, only slightly less important, that I'd be able to accomplish my personal goals earlier in life than "at the end".

My list actually wasn't that difficult to come up with, as I'm sure other people will discover as well, because many of these were already passions I was unwilling or unable to indulge in thus far in my life. In the process, I formulated a list of four things I'd spent my lifetime up to that point dreaming about but not believing I could do. My reasons for not doing them stemmed from a) the expense involved, b) the lack of time to undertake them, and c) being very aware that it takes me a long time and a whole lot of effort to learn new things (in part because I was already 45 years old when I embarked on this).

Unofficially, I suppose the first real bucket list wish I made started with writing. I wrote (and illustrated) my first story when I was eight, and I always knew that was what I wanted to do more than anything else. There was little if any encouragement around me for this endeavor but, in the defense of my friends and family, becoming a success in this field isn't exactly a stable environment or income. When I was 20, I was determined to make a go of it regardless. My first book was published when I was 27…just after I'd made the heartrending decision to quit writing because I'd already invested nearly a decade attempting and failing to get published. Sometimes it takes that kind of irony to kick you in the pants and inspire you to reach for more. I spent the next 27 years of my life setting goals and pouring my all into making something of my writing. As I near the end of my writing career at the age of almost 55, my published credits in most every genre imaginable have passed 150 titles and these have garnered nominations or wins for over 130 awards.

The bucket list of lifelong passions I officially came up with after watching The Bucket List was quickly assembled (written down here years later in all the detail I imagined from its origin), prioritizing my wishes according to my deepest desires:

#1: Learn to play piano. I've loved music all my life. I can't stand silence so music fills all my waking moments. I wasn't allowed to learn an instrument in school, and I'd wanted to from the moment the possibility was brought up. My goal in doing this wasn't fame or to perform in a professional setting. It would only ever be for private enrichment and perhaps to accompany family and friends--many of them musicians.

I started small with the first Alfred's Piano instruction book and my son's discarded keyboard. I practiced every day, teaching myself from the manual and asking my guitar- and saxophone-playing husband (who was part of the praise team band at our church) for help whenever I needed it. Naturally, that keyboard quickly didn't have what I needed to advance (88 keys and pedals), but a generous gift allowed me to purchase the beautiful piano I now cherish. I also started taking piano lessons nearly a year into my efforts and took them for more than four years. When my instructor moved away, I went back to teaching myself.

At the time I started, I committed myself to this, my #1 bucket list priority, and I was disciplined in daily practice and learning as much as I could about all aspects. I knew going into it that it would be the biggest challenge of my life, and, boy, was (and is) it. But it's worth it. Eight years in, and I'm still learning, still developing, still passionate about it, and it's something I'll do, and enjoy, until the day I die.

#2: Develop my drawing and artistic skills across many types of media. I've been writing children's books as long as I can remember, but finding someone to illustrate them hasn't been easy. I've had many stories that I've written that I couldn't get anyone to provide artwork for so they're sitting in my story cupboard, unpublished. In the past, I often wished that the fledgling talent I've had all my life in this field could be cultivated and honed into true ability. While I didn't at first intend to make illustrating children's books a career, when I made my decision several years ago to retire from writing soon, I realized that it was exactly what I wanted to do once I've completed the last of my book 16 series.

I started slow and cheap. Using inexpensive pencils and drawing pads or typing paper I already had lying around the house, I randomly drew whatever inspired me whenever I had downtime from writing. In the first year I undertook this, I produced a few good things. I wasn't trying to do anything serious beyond seeing what I could accomplish and what my strengths and weaknesses were. I knew if I let myself get too excited, it would interrupt my writing, and I didn't want to do that, considering I was counting down to completing my last several novels. I wanted to devote myself to making those stories the best they could be.

Last year, finding myself slowing down in general with nearly everything in my life, recovering from writing projects became much more difficult for me. I needed longer breaks and other ways to relax in between projects. I invested a bit more time and money into my artistic endeavors. I found a place that offers affordable DVD/streaming courses taught by some of the best experts in their respective fields and purchased three art classes on drawing, pencil coloring, and painting. These could be done as I had time and I could set my own pace. I purchased artist grade pencils, paper, and other supplies and equipment. Additionally, I reworked my daily and yearly goals to include times of writing and times of art. I also decided to bring along my readers on this endeavor by posting my art (such as it was) on my Facebook page. The response has been both motivating and moving.

As my artistic abilities grow, I'm finding the process hard, but also realizing I can do things I could never have imagined I was capable of in the past. At the moment, I'm still reining in how much time and effort I devote to these endeavors, but I'm only a few books away from finishing the last of two series. Until then (mid-2024, if I stay on track with my goals), I'm applying myself to learning and honing my artist talents in the time I've allotted to it each day, week, or month, so, by the time I'm ready to get started illustrating my first children's book, I'll have a wide variety of mediums I'm skilled enough in to utilize.

#3: Learn a second language. I took a year of French in high school and I was actually really good at reading and writing the language, just not speaking it. When it started getting mathematical (the way they do numbers is hard!), I dropped out. I've regretted my decision not to continue. My husband is very good at languages--he taught himself ancient Greek and he's using a program that makes learning a language fun and easy to advance for Spanish. He's constantly asking me to join him in the program, but with writing, piano, and art in my daily life taking up most of my time and energy, I'm spread a little thin. I used to have a friend who spoke native Spanish, and I always wished I could understand her when she talked to her family in the language. That would have been the perfect time to start learning, as I could have gotten real feedback and help in learning, but I was motivated at that time. After I retire from writing, I'll have one less thing on my plate and I expect I'll get involved with the program hubby's using to learn Spanish at that point. (I do actually have a loose goal of 2025 set to start this.)

#4: Learning. Just learning. Like most people, I have a lot of random interests that I've never had a lot of time to explore--learning to sing professionally (I do have natural talent in this regard, luckily) as an accompaniment to playing piano, finding out more about unique periods of history (Medieval specifically), geography, space, art culture, and science. The place where I got my art DVDs offers courses in a lot of these disciplines that interest me. I don't currently have a lot of time, but I've already mentioned that I don't care for silence. Usually I fill it with music or art lessons. However, there are frequent slots in my day where I could easily be listening to a lecture, learning more about any one of these random interests. I always want to be learning new things that may inspire any of my other abilities to new heights of creativity. That said, I wouldn't undertake this goal until I'm well into learning a second language.

Next week we'll talk about strategies in taking the next step toward achieving the goals in your life you're most passionate about seeing fulfilled.

"Seize the life and the day will follow!" ~Linda Derkez

Karen Wiesner

is an award-winning, multi-genre author of over 150 titles and 16 series.

Visit her

website here: https://karenwiesner.weebly.com/

and https://karenwiesner.weebly.com/karens-quill-blog

Find out more about her books and see her art here: http://www.facebook.com/KarenWiesnerAuthor

Visit her publisher here: https://www.writers-exchange.com/Karen-Wiesner/