How To Learn To Write

Part 2

How do writers influence their audience?

Part 1 is

https://aliendjinnromances.blogspot.com/2012/07/how-to-learn-to-write.html

Part 2 is my answer to a question on Quora.

https://www.quora.com/How-do-writers-influence-their-audience

On Quora, George Ireland requested my answer to the following question:

How do writers influence their audience?

John Joss a nonfiction and novel writer, journalist, answered very correctly,

------quote-----

Writers in any medium—technical writers, journalists, poets, advertising copywriters, PR writers, film and television writers, speech writers, business-proposal writers, nonfiction or novel writers—influence their audiences by having mastery over grammar, syntax, spelling and vocabulary. They also have a clear understanding of the needs of their audience(s). Then they apply pen or pencil to paper, or fingers to keyboard, and write the correct words that address the subject with brevity and clarity in terms that they know that audience can grasp and will ‘act’ upon.

------end quote-------

And all of that craftsmanship and skill set acquisition applies equally to fiction writing.

However, fiction never works well if the author writes consciously to influence the reader, or spur to a specific action the writer has selected. It comes off preachy, exposition heavy, abstract, and even insufferably arrogant (read Ayn Rand for examples). Characters seem wooden, two-dimensional, stiff, cardboard, and cliche.

Reading fiction is taking a ride in a Character’s head — or perched on a shoulder.

Reading fiction is always an adventure, leaping out of the everyday existence and into a situation or problem entirely outside the reader’s experience. It may be a situation the reader would like to visit in reality (such as a Romance) or it may be one they’d never, ever, want to visit (a cautionary tale such as Orwell’s 1984).

The writer defines the Character, and the resources of material goods, talents that may lie hidden, skills already proven, aspirations driving the character toward a goal, just as the player does when entering a Game.

Within these parameters of personality and resources, the character must solve the problem, resolve the conflict, and make some progress toward the aspiration. If you can’t get there from here, the novel is about going somewhere else to start over. But it is progress.

The novel may be about redefining what goals would be satisfying or worth while — such as a Law Student who drops out of school to raise kids. Sequels might be about the Law Student joining the PTA then running for School Board, then Legislature, maybe national office after that - maybe finishing the Law degree while the kids are in High School.

A reader whose life is stalled always enjoys working the problem of a Character who is acting to break out of a stall.

Such an adventure inside the mind and life of a Hero might seem like it is an “influence” spurring a reader to pick up the pieces of their own broken life and move on. But that isn’t what the writer is doing.

The writer is selling FUN - entertainment - and if you don’t have FUN you can’t sell it, and you certainly can’t deliver what you don’t have in stock. So the writer is not selling INFLUENCE when writing fiction — it’s no fun to “be influenced” — it is lots of fun to gain a more dimensional understanding of yourself, your world, and the goals you might choose to drive toward.

By reading fiction, a person can gain enough perspective on the world to define their own real-world options as a problem to be solved. Riding in the head of a character who is working out (usually by trial and error; sometimes by being instructed) a methodology of problem solving and techniques of conflict resolution, can inspire (not influence, inspire) a reader to attempt some real-life experiments.

Now here’s the trick.

The writer must have a clear vision of the “world” they are inviting the reader into. The writer must evoke (not describe, summon) the fictional world in such a way that the reader can recognize it as possibly somewhat like their own everyday-life, but different. The writer must know, understand, grok, comprehend that difference so completely that, without effort, the writer transmits the specific, singular, vividly portrayed difference that distinguishes the fictional reality from everyday reality while at the same time asking the question — is it distinctively different?

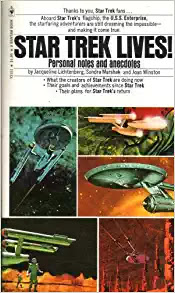

This is what I learned from Gene Roddenberry while doing the multitudinous interviews for STAR TREK LIVES!

— good fiction doesn’t TELL the reader the answer to the mysteries of life. Good fiction asks questions. Good fiction re-phrases the questions the reader has been pondering. Good fiction questions the viewer’s assumptions about reality, about life. Good fiction poses old questions in new forms and leaves the viewer to chew it all over.

Good fiction does not choose the answer for the reader, or limit what the “right” answer might be.

Good fiction, I learned from Leonard Nimoy while doing interviews, is “open textured” — giving an outline and inviting the viewer to fill in with their own imagination.

Good fiction does not “influence” but rather inspires and motivates. Robert Heinlein inspired, as did Star Trek, many readers to major in math, science and engineering.

Jacqueline Lichtenberg

http://jacquelinelichtenberg.com