Based on Writing the Standalone Series (formerly titled Writing the Fiction Series {The Guide to Novel and Novellas})

“Straddling the fence”--when multiple genres make an appearance in a series and even in a single book--is becoming more and more common these days. Not only common, but in some ways irreverent and possibly even over-the-top, especially when you consider Seth Grahame-Smith’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Quirk Books, the publisher of these hybrid novels that combine Classic novels with mania and pop culture horror, also publishes Ben H. Winters Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters and others like it.

In most cases, however, the combination of genres in a novel or series isn’t so strange. After all, what goes together better than romance and suspense? These are two distinct genres, and yet they make perfect sense when paired either in a single book or separately in a series. It’s also not much of a stretch to combine historical and time-travel fiction in a series. But what happens when a series that started out as contemporary fiction suddenly dives into the pools of the supernatural or historical? Does that work? Or will you lose readers who expected one thing and got quite another? Among the authors and publishers I interviewed about this topic, the responses were about as varied as genres can sometimes be.

Some authors weighed in against changing genres from one book to the next in a series. Luisa Buehler says, “Readers expect a series--that starts as one basic genre--to stay that way. It’s unfair to set them up for a traditional mystery with no graphic violence, sex, or language, then shift to a serial killer who kills brutally in great description.” N.J. Walters went further: “You have to always keep your readers in mind. They’re expecting something particular when they read a series. If all the books in the series are contemporary, for example, it would be strange to throw a paranormal in there. You’ll probably get readers who don’t like the paranormal and would be disappointed. In my opinion, a writer owes it to the readers not to change midstream. If you want to write a different genre book, then write one. Make it a standalone, or start a new series.” Vijaya Schartz agrees, “I discovered that, at least within a series, you want to remain in the same genre. Readers are funny that way. They expect the same atmosphere, the same type of story, and, if you switch gears on them, they’ll not only notice, but they might resent you for it. I write in various genres (contemporary romantic suspense, paranormal romance, sci-fi, fantasy romance, etc.) and I noticed that my readers do not always cross over from one genre to another. They know what they like, and that’s all they want to read.” Publisher Laura Baumbach adds, “Readers have expectations once they start a series, and I believe in giving them what they want. The series needs to stay on track and stick to one genre.”

Consider that librarians and bookstore owners won’t know how to shelve books that lump too many genres into one. While no one wants to be pigeonholed, it’s what often happens in the distributor setting of selling books.

Despite the arguments against multigenres in one series, many of the authors and publishers I interviewed saw no problem with crossing genres within the books in a series. Fantasy and mystery author Fran Orenstein says, “Overlap adds depth and interest. Why can’t fantasy have romance, or mystery have comedy?” Luisa Buehler, while against major leaps, advocates “stretching the basic genre.” Cat Adams believes that “Readers today are, for the most part, willing to ignore bookstore shelving requirements to expand their vision.” Publisher Miriam Pace refuses to pigeonhole her authors. “I want them to show me how versatile they are. I feel the more stories they can write in different genres, the wider their readership.” Fellow publisher J.M. Smith takes a practical approach to this: “It’s okay to mix genres as long as you have one that continues throughout. For instance, Wild Horse Press publishes the Ashton Grove Werewolves Series which is predominantly paranormal but there are a few books in the series that have fantasy and science fiction thrown in as well, with fairies, sorcerers, psychics, etc.” We’ve stressed that there are no rules, right? Charlotte Boyett~Compo puts this into perspective when she says, “While I appreciate my readers’ opinions, I’m not writing the books with that in mind.”

Authors of series do have to write a story the way it needs to be written ... even if it ends up leaving the domain of the genre we started the series in. One way to handle this is to plan the series carefully. When I was writing my Wounded Warriors Series, I knew that one of the characters was psychic. I set up this detail in the first two books before I got to her story, and, when this contemporary women’s fiction/romance series reached the third book, Mirror Mirror, I think readers were prepared for a journey into the supernatural because I’d already established it in advance. I don’t believe it would have worked if I hadn’t planted that arc right away. Incidentally, while I didn’t return to the supernatural in the next three books, I also didn’t hide from the fact that this middle story contained it. How well executed something like this is in a series story is always determined by how well you set it up in advance.

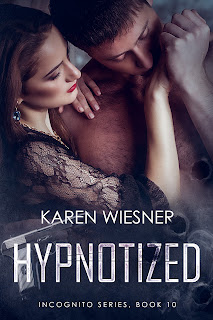

I did the same thing in the tenth book in my Incognito Series (reissue release date TBA), which are basically action-adventure/romantic suspense novels. In Hypnotized, I introduced the concept of mind-reading within the background of using the “technology” for terrorism. The reviews and reader feedback I’ve received have convinced me this worked for Hypnotized regardless of how unlikely it was to find a book with a somewhat supernatural plot thread near the end of the long series. I also think this genre-straddling worked in part due to the fact that, within an author’s note that preceded the story, I included actual reports of the United States military attempting to develop a technique for mind-reading. This grounded the “supernatural” premise in fact, and the story mirrored this. The supernatural element was reality-based and therefore fit the series premise naturally.

In any case, I believe it’s true that some genres simply lend themselves to straddling extremely well. Romantic fiction can fit well with most, if not all, other genres. Mysteries have also proved to be easily stretched in this regard. One example is Carrie Bebris’ respectfully rendered and amazingly executed Mr. & Mrs. Darcy Mystery Series, which remains true to Jane Austin’s romance novels but presents a mystery to unravel that occasionally has a believable paranormal twist.

If genre straddling was a complete no-no, it would make no sense that historical mysteries are so popular these days. Time-traveling elements are also being effectively woven into any and every genre convincingly, including romance, historical, suspense, speculative fiction, and countless young adult series.

I think we can conclude that authors don’t

need to follow too many rules when it comes to straddling genres, but they must

keep readers in mind when doing anything off-the-wall. If you lose more readers

than you gain, what’s the benefit?

Karen S. Wiesner is the author of Writing the Standalone Series, Volume 3 of the 3D

Fiction Fundamentals Collection

http://www.writers-exchange.com/3d-fiction-fundamentals-series/

https://karenwiesner.weebly.com/writing-reference-titles.html

Happy reading!

Karen Wiesner is an award-winning, multi-genre author of over 140

titles and 16 series, including HYPNOTIZED,

Book 10: Incognito Series

https://karenwiesner.weebly.com/incognito-series.html