Of

Arcs and Standalones, Part 3:

Establishing a Series Arc Early in the Writing Process

This is the ninth of fifteen posts dealing with surprising things I learned in the course of writing a science fiction series.

In the initial part of this 6-part article, we started defining story arcs followed by series arcs. This time we're going to start laying the groundwork for the series arc before we do the same for story arcs with a technique and examples. This is something that it's always preferable to start as early in the writing process as you can--ideally, long before you actually begin writing the first draft. The series arc is the umbrella all your story arcs will fit under, so it makes sense to do that first.

The easiest way to discover your overall series arc is to know what connects all the books.. In this way, you can make sure the series arc runs its proper course through each book in the series until it's resolution in the last book. Establishing the basics for each book in the series can give you countless insights for far-reaching possibilities as you prepare to write each new installment.

The first step is to blurb the series. The series blurb should tell readers how all the books in that series are connected. Most series blurbs range from one to four sentences. Science fiction, fantasy, and historical books in a series may well require longer series blurbs. That's because the series blurb has to make sense of whole worlds, cultures, events, and conflicts, which, in many cases may seem vastly different from those a modern reader is accustomed to. If readers don't understand the premise of your series in the series blurb, they may not bother reading the first book.

When I come up with a series, I almost always have what some writers would consider a freakishly good idea about what will happen in each of the installments. Just prior to the summer of 2018, when I started advance research on my sci-fi series, I had more than enough details at that point to be able to blurb my series arcs filling in the blanks of this worksheet:

Who

_____________________________ (Series Main Character{s})

What

_____________________________ (Conflict or Crisis)

Why _____________________________ (Worst Case Resolution Scenario)

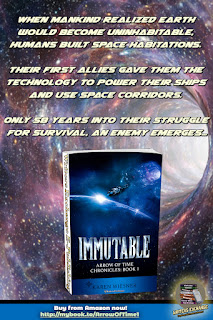

In the previous post, I talked about the three series arcs in my Arrow of Time Chronicles, one of the major and two of them minor. All three of these series arcs were introduced in the first installment in the series, touched on in different degrees over the course of the middle two books, but only resolved in the final story in the series. Nevertheless, although I knew they'd all be important within the individual stories, I felt like adding the third series arc to the series blurb overcomplicated it so I left it out. Here's the form filled out for Arrow of Time Chronicles:

Who Mankind (Series Main Character{s})

What When mankind realized Earth would soon become uninhabitable, Humans formed a cooperative central nexus in order to save themselves from certain extinction. Together, they built and transferred their population to massive space habitations in orbit of their planet and as many as possible revolving around the other planetary bodies in the Sol System. Only fifty-eight years into their desperate struggle for survival, a hostile enemy with Napoleonic ambitions emerges as a yet another threat to not only mankind's survival. (Major Conflict or Crisis)

A cataclysmic organic menace is beginning to be recognized, ensuring the total annihilation of every living thing in the universe if, together, they can't find a way to stop it. (Minor Conflict or Crisis)

Why The peace mankind has begun to forge with allies from other planets around the galaxy is jeopardized as questionable agendas and hidden motives are unveiled. (Major Worst Case Resolution Scenario)

Why The organic menace threatens the total annihilation of every living thing in the universe if, together, mankind and its allies can't find a way to stop it. (Minor Worst Case Resolution Scenario)

Below, you'll see the Arrow of Times Chronicles series blurb I eventually modified and refined the worksheet components to come up.

Arrow of Time

Chronicles

by Karen Wiesner

A timeless universal truth: No simple solutions, no easy answers, and nothing is ever free…

When mankind realized Earth would soon become uninhabitable,

Humans formed a cooperative central nexus in order to save themselves from

certain extinction. Together, they built and transferred their population to

massive space habitations in orbit of their planet and as many as possible

revolving around the other planetary bodies in the Sol System. They also constructed

spacefaring "liveships" in hopes of traveling through the galaxy in

search of new homes. Unbelievably after almost a hundred years, their

communications sent out into the farthest reaches of the universe to discover

other intelligent life secures an audience. Their first allies arrived in

mankind's solar system in 2073 and shared their knowledge, technology and

resources to not only power their liveships for swift navigation through space

corridors that fold space and time but also provided the scientific

advancements necessary to eventually heal their dying planet.

Though mankind has a brand-new shaky start, strong potential alliances, and hope for tomorrow, only fifty-eight years into their desperate struggle for survival, a hostile enemy with Napoleonic ambitions emerges as a yet another threat to not only mankind's survival, but also that of their associates who have faced the aliens in times past. Abruptly, the peace the allies have begun to forge is jeopardized as questionable agendas and hidden motives are unveiled. In the wake of these very real, immediate threats a cataclysmic organic menace is only beginning to be recognized, ensuring the total annihilation of every living thing in the universe if, together, they can't find a way to stop it.

Next week, we'll talk about how to establish your story arcs early in the writing process and use this same technique in an example.

Happy writing!

Based on Writing the Overarching Series (or How I Sent a Clumsy Girl into Outer Space): 3D Fiction Fundamentals Collection by Karen S. Wiesner (release date TBA)

https://karenwiesner.weebly.com/writing-reference-titles.html

http://www.writers-exchange.com/3d-fiction-fundamentals-series/

Karen Wiesner is an award-winning,

multi-genre author of over 140 titles and 16 series, including the romantic science fiction series,

ARROW OF TIME CHRONICLES

https://www.writers-exchange.com/arrow-of-time-chronicles/

https://karenwiesner.weebly.com/arrow-of-time-chronicles.html