A robotic device called ElliQ, which functions as an AI "companion" for older people, is now available for purchase by the general public at a price of only $249.99 (plus a monthly subscription fee):

Companion RobotAs shown in the brief video on this page, "she" has a light-up bobble-head but no face. Her head turns and its light flickers in rhythm with her voice, which in my opinion is pleasant and soothing. The video describes her as "empathetic." From the description of the machine, it sounds to me like a more advanced incarnation of inanimate personal assistants similar to Alexa (although I can't say for sure because I've never used one). The bot can generate displays on what looks like the screen of a cell phone. ElliQ's makers claim she "can act as a proactive tool to combat loneliness, interacting with users in a variety of ways." She can remind people about health-related activities such as exercising and taking medicine, place video calls, order groceries, engage in games, tell jokes, play music or audiobooks, and take her owner on virtual "road trips," among other services. She can even initiate conversations by asking general questions.

Here's the manufacturer's site extolling the wonders of ElliQ:

ElliQ Product PageThey call her "the sidekick for healthier, happier aging" that "offers positive small talk and daily conversation with a unique, compassionate personality." One has to doubt the "unique" label for a mass-produced, pre-programmed companion, but she does look like fun to interact with. I can't help laughing, however, at the photo of ElliQ's screen greeting her owner with "Good morning, Dave." Haven't the creators of this ad seen 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY? Or maybe they inserted the allusion deliberately? I visualize ElliQ locking the client in the house and stripping the premises of all potentially dangerous features.

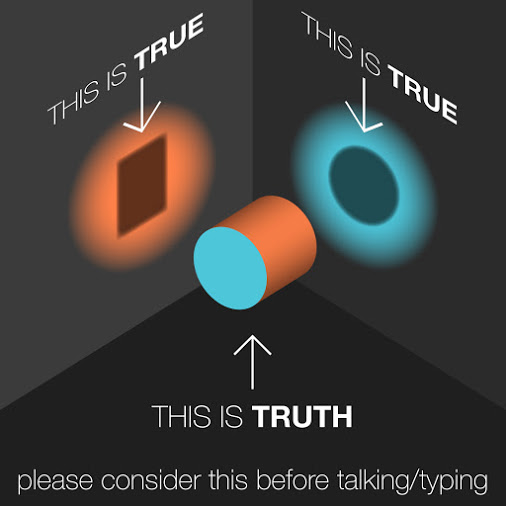

Some people have reservations about devices of this kind, naturally. Critics express concerns that dependence on bots for elder care may be "alienating" and actually increase the negative effects of isolation and loneliness. On the other hand, in my opinion, if someone has to choose between an AI companion or nothing, wouldn't an AI be better?

I wonder why ElliQ doesn't have a face. Worries about the uncanny valley effect, maybe? I'd think she could be given animated eyes and mouth without getting close enough to a human appearance to become creepy.

If this AI were combined with existing machines that can move around and fetch objects autonomously, we'd have an appliance approaching the household servant robots of Heinlein's novel THE DOOR INTO SUMMER. That book envisioned such marvels existing in 1970, a wildly optimistic notion, alas. While I treasure my basic Roomba, it does nothing but clean carpets and isn't really autonomous. I'm not at all interested in flying cars, except in SF fiction or films. Can you imagine the two-dimensional, ground-based traffic problems we already live with expanded into three dimensions? Could the average driver be trusted with what amounts to a personal aircraft in a crowded urban environment? No flying car for me, thanks -- where's my cleaning robot?

Margaret L. Carter

Please explore love among the monsters at Carter's Crypt.