There's an essay on the WRITER'S DIGEST website called "The Importance of Character Growth in Fiction," by bestselling author Annie Rains:

Importance of Character GrowthShe lists and discusses vital elements in showing the transformation of a character over the course of a story: Goal and motivation; backstory and the character's weakness or fatal flaw, arising from features of the backstory; the plot and how its events force the protagonist to struggle, plus the importance of pacing so that growth doesn't "happen in clumpy phases"; the "ah-ha" moment when the character realizes the necessity of taking a different path; importance of showing through action how the character has changed to be able to do "something that they never would have been able to do at the book’s start."

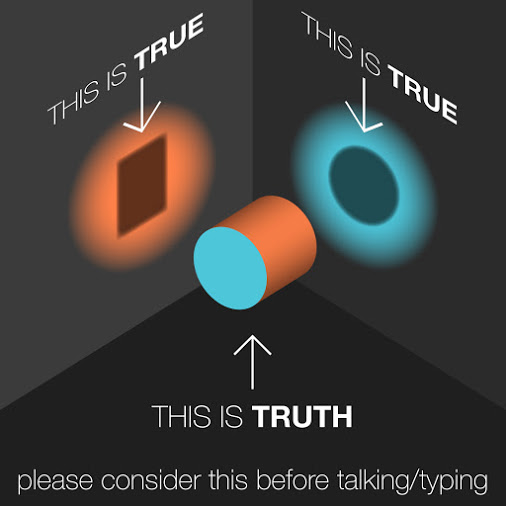

As vital as all these factors are, and as much as I love character-driven fiction myself, I have slight reservations about Rains's opening thesis: "If your character is stagnant, there is no story. . . . Your character should not come out of your plot as the same person they were before their journey began." Doesn't good fiction exist to which this premise doesn't apply? Classic detective series, for example. What about Sherlock Holmes? Hercule Poirot? Miss Marple? What about action-thriller heroes such as James Bond? Through most of the series, Bond survives harrowing adventures that would kill ordinary men many times over, with no discernible change in his essential character. (In the last few books, he does begin to change.) Even in stand-alone novels, as mentioned in the WRITER'S DIGEST essay to which I linked in my blog post on July 20, static characters (as opposed to the negative term "stagnant") have their place. In A TALE OF TWO CITIES, Charles Darnay doesn't change, whereas Sidney Carton does. In THE HUNT FOR RED OCTOBER, the Russian submarine captain has already made his life-changing decision before the story begins and never veers from his goal. In A CHRISTMAS CAROL, Scrooge transforms, while Bob Cratchit is a static character. So, arguably, is Romeo, who's still the same impulsive, emotion-driven youth at the end of the play as at the beginning, thereby possibly triggering his own tragic end.

I'd maintain that, while Rains is self-evidently correct that a character's circumstances have to change in the course of a narrative, he or she doesn't necessarily have to undergo a transformation, depending on the genre. The character must either attain the plot's stated goal or fail in an interesting, appropriate way. Without a change in his or her situation, whether external, internal, or both, there's no story. But an internal transformation isn't a necessary feature without which "there is no story."

Margaret L. Carter

Please explore love among the monsters at Carter's Crypt.