This is the name of a page on the TV Tropes site, referring to the countless works of fiction with authors, playwrights, screenwriters, journalists, or poets as protagonists, a not unreasonable consequence of the hoary precept to "write what you know.":

Most Writers Are Writers

Taking this principle to its logical extreme leads to the situation satirized in a quote from SF author Joe Haldeman at the top of that trope page: "Bad books on writing and thoughtless English professors solemnly tell beginners to Write What You Know, which explains why so many mediocre novels are about English professors contemplating adultery."

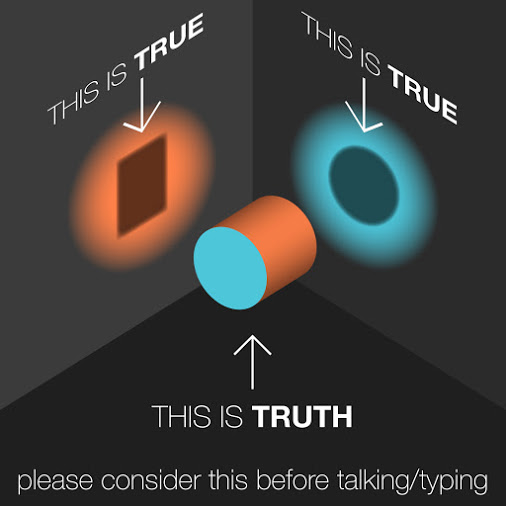

Strict obedience to that "rule" would, of course, mean no fiction could be created about places or ethnicities other than the author's own, much less science fiction or fantasy. TV Tropes has another page discussing, with examples, the difficulties of writing about nonhuman protagonists such as extraterrestrials or animals. Yet even these characters have to exhibit as least some human-like traits, or readers couldn't identify with them:

Most Writers Are Human

Henry James critiques the advice that an author should write only from his or her own experience in this famous passage from his 1884 essay "The Art of Fiction" about the need for a writer to be someone "on whom nothing is lost":

"I remember an English novelist, a woman of genius, telling me that she was much commended for the impression she had managed to give in one of her tales of the nature and way of life of the French Protestant youth. She had been asked where she learned so much about this recondite being, she had been congratulated on her peculiar opportunities. These opportunities consisted in her having once, in Paris, as she ascended a staircase, passed an open door where, in the household of a pasteur, some of the young Protestants were seated at table round a finished meal. The glimpse made a picture; it lasted only a moment, but that moment was experience. She had got her impression, and she evolved her type. She knew what youth was, and what Protestantism; she also had the advantage of having seen what it was to be French; so that she converted these ideas into a concrete image and produced a reality. Above all, however, she was blessed with the faculty which when you give it an inch takes an ell, and which for the artist is a much greater source of strength than any accident of residence or of place in the social scale. The power to guess the unseen from the seen, to trace the implication of things, to judge the whole piece by the pattern, the condition of feeling life, in general, so completely that you are well on your way to knowing any particular corner of it--this cluster of gifts may almost be said to constitute experience, and they occur in country and in town, and in the most differing stages of education. If experience consists of impressions, it may be said that impressions are experience, just as (have we not seen it?) they are the very air we breathe. Therefore, if I should certainly say to a novice, 'Write from experience, and experience only,' I should feel that this was a rather tantalising monition if I were not careful immediately to add, 'Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost!'"

To put it more briefly, it has been said that instead of "Write what you know," the rule should be, "Know what you write." In other words, thoroughly research whatever you aren't already familiar with from personal experience or study.

I admit I've usually adhered to "write what you know" in terms of my characters' occupations. Most of my heroines work as librarians, proofreaders, bookstore clerks, college instructors, or, yes, authors. Since their work usually isn't the central focus of the story, I figure it's just as well to give them jobs I know enough about not to make blatant errors. Where the protagonist's vocation does play a major role in the plot, I default to "writer."

The internet makes research easier than ever before, provided one takes care to distinguish accurate sources from their opposite. And for in-depth exploration, reliable websites can direct the searcher to books, which can often be obtained through interlibrary loan—which can also be arranged online. A public library might even have access to that one necessary book in electronic format, eliminating the need to go out to pick it up. For example, once when I wanted to insert a few sentences about a heroine's psychic vision of a mountain trail in Afghanistan into a story, typing and clicking on a single search phrase gave me all the images I could wish for. We truly live in wondrous times for "knowing what we write."

Margaret L. Carter

Carter's Crypt