How Do You Know If You've Written A Classic

Part 7

How Do You Know These Two Are Soul Mates?

Previous Parts in this series are indexed here:

https://aliendjinnromances.blogspot.com/2020/03/index-to-how-do-you-know-if-youve.html

Opposites attract, but do they always make a good team?

It is Ancient Wisdom that you shouldn't marry someone expecting them to "change" -- or expecting you can "change him."

But people do change, and the velocity of change can be ferocious during early life development (which is why we avoid marrying too young), and oddly enough, during the elder years (with the Second Time Around story).

It is said that if you're not a Democrat or Socialist when you're in your twenties, you have no heart, but if you're not a Republican or Capitalist when you're in your fifties, you have no brains.

Ferocious attention has been devoted to proving or disproving this notion that maturity dictates an individual's view of how society should govern itself.

In 1962 John Crittenden published a paper based on research funded by an award of a Law and Behavioral Science Fellowship at the University of Chicago Law School.

https://academic.oup.com/poq/article-abstract/26/4/648/1868747

The way party affiliation, or political views, tend to correlate with age has been a focus ever since.

Recent studies have shown that today people don't change their politics when they move to a state dominated by the other party, and people do not shift from progressive to conservative (or any other pair of polar opposites) of opinion as they age.

Science fiction writers ask: "Well, maybe they did shift, but they don't now. Why? What changed?"

Maybe there has been that kind of change in human nature, or maybe not.

Writing Science Fiction Romance will bring you to wrestle with the adage that human nature never changes. Science Fiction is about science impacting human cultures.

See Part 18 of the Targeting a Readership series - Targeting a Culture

https://aliendjinnromances.blogspot.com/2020/03/targeting-readership-part-18-targeting.html

Cultures change -- but the basic nature of the humans who form the culture doesn't change much. What does happen, over 280 year spans or multiples of that) is a shift in emphasis in a human generation. What people all born in the same 20 year span think or feel is most important, most critical, most consequential. Or in other words, what bothers them the most.

For that reason, we tend to make marriage matches with people of about the same age, and from the same culture (if not country).

Within the parameters of politics and generation, a person can find their match much more readily. Many matches work just fine for all the decades of life to be lived, but a good match can be torn apart if one of the couple finds an actual Soul Mate.

Often, a couple merely matched will break up when one of them becomes so deeply infatuated (at a later age, it's really hard to admit to a teenager syndrome of infatuation) with another person, and believe they have found a Soul Mate.

A writer exploring the making and breaking of a marriage, in any setting and time, has to convince the current readership of the Soul Mate status.

It is possible for Soul Mates to stray because of an infatuation - what happens then? Does the marriage break then reform?

How does a person who is caught deep into an infatuation discover that the object of infatuation is not the Soul Mate they seem to be?

What is the diagnostic test for Soul Mating?

What will the reader accept as proof?

Today, families are riven apart by politics and arguments about how ethical, moral, or intelligent those who support one view (or the other) are. The view espoused over the family dinner table can label a person so "deplorable" they will never be welcome in this house again.

So the problem, even if the hosting couple are genuine Soul Mates, becomes how do you change your in-laws' minds about an issue of right/wrong ways of thinking, of solving ethical dilemmas?

Such a dramatic scene, played out in show-don't-tell, in symbolism and dialogue, and storming out of the room, and returning in a different mood, and maybe pulling down reference books to prove a point, may become our next towering Classic that lasts forever.

To convince your reader that two Characters are true Soul Mates, show them handling such a delicate, strife-ridden family scene.

That scene would be the middle of a Happily Ever After novel, an epic fail of family bonds.

Say, for example, this family dinner were the celebration of a young couple's engagement where they are discussing Setting The Date.

The first half of the novel has to reveal the reasons why each of the family members holds the view of right/wrong that they do -- the view of justice, and the correct way to proceed with the wedding plans. If the family is large enough, you can bet any date chosen will exclude someone.

It has to be soon because so-and-so is thinking of entering Hospice.

It has to be later because so-and-so has a scholarship for a year in school in (some exotic place that will give them major credential in job hunting - say Tokyo?).

It has to be here because most of us live here.

It has to be there because so-and-so can't travel.

It has to be somewhere else cheaper, or where the weather is nice that time of year.

Or if someone is running for public Office, there will be political reasons for place, date, and timing, possibly even religion or lack thereof could figure.

Watching this family define and solve the problem will telegraph to the reader which couples are actual Soul Mates -- and which are likely to break up next.

The first half of the novel reveals how each faction in the family arrives (by reason, by emotion, by unthinking commitments) at their stances on the matter.

The Soul Mate parent-couple in the family will show-don't-tell the solution, and lead all the factions toward each other.

This could take several chapters -- as groups break away and reform in the kitchen, the back porch, the front yard, even the garage to show off a new car, or one being fixed.

The Soul Mates won't impose their solution on the engaged couple, but rather bring up the basic principles they have always taught their children for social and family problem solving.

If the reader agrees with those principles, the reader will likely believe the elder couple are Soul Mates -- and by association, that the married-children of that couple are likewise Soul Mates.

For contrast, at least one couple should be merely a good match with a solid working relationship.

The second half of the book is all about the engaged couple trying to make the family chosen date-time-place actually work for them. How they go about making the adjustments will reveal to the reader whether this young couple are Soul Mates.

Soul Mates fight each other harder and hotter than any other sort of partner. But the fire exploding through their arguments heals rather than wounds.

Soul Mates argue - but they don't fight. And they argue all the time over everything. Vociferously. Adamantly defending their positions. Stubbornly returning to that position. All until they suddenly discover the error in their argument - then they change their mind and immediately admit that out loud.

A Soul Mate might not behave that way with anyone else, might fight all the time with others, concede or crow victory, and just be obnoxious about it. But that behavior would change when in the presence of the Soul Mate.

The second half of the novel would include the engaged couple arguing shown in high contrast to another couple in the wedding party who fight each other over the same issue (e.g. which restaurant should the dinner be at).

The couple that fights, and simply can't be guided into arguing, ends up in divorce court just before the Soul Mates' wedding, while the couples that argue show up at all rehearsals and do their jobs smoothly.

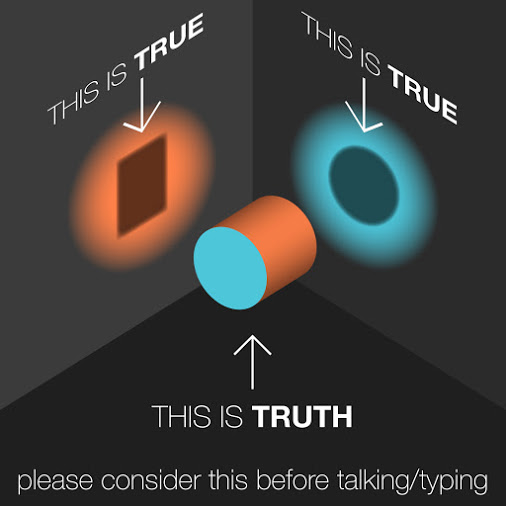

What is the difference between an argument and a fight?

An argument is about what is right.

A fight is about who is right.

When it's about who is right, it is all about power, dominance, and avoiding confronting emotions.

When it is about what is right, it is all about the mutually shared, urgent, burning desire to choose right over wrong.

That is how Soul Mates are distinguished from other couples, and, whether they are conscious of it or not, readers can see the difference.

Sorting out right from wrong is hard, and humans rarely agree on how to apply those principles to solve real world problems (like choosing a restaurant).

The symbolic difference between fighting and arguing is simply whether the pair doing the shouting are articulating their reasons for their stances, then delineating why the other person's reasons don't apply to this case, or how that reason is based on a fallacy.

Soul Mates argue, destroying each others' reasons for holding a position, until they both agree -- often they evolve to agree on something neither knew before, or would have adopted as a position.

When Soul Mates argue to a conclusion, they are each thankful to the other for imparting new information or correcting an error. Learning from a Soul Mate is a great joy, not an ignominious defeat that leads to subjugation.

A mismatched couple will fight, and if one of them always wins, the marriage will likely break up unless one of them prefers being subjugated.

Marriages based on a good match generally go through many fights, many arguments, ending with a basic score of 50/50, keeping the balance so neither is subjugated.

To convince readers your Soul Mates are genuine, you need contrasting couples, contrasting families, and contrasting Singles, divorcees, widows, etc. We need to see them all fighting, arguing, and settling the matter to see the stark difference in methodologies.

The future Science Fiction Romance Classics will lay out this pattern around at least one Human/Alien couple.

The Classic that defines the field will (maybe already has) illustrate the nature of Soul Mates by how they go about solving problems using an Alien methodology.

My candidate for CLASSIC SCIENCE FICTION ROMANCE is the Alien Series by Gini Koch -- #16 came out in February 2018

https://www.amazon.com/Aliens-Abroad-Alien-Novels-Book-ebook/dp/B06XJYL8LY/

Jacqueline Lichtenberg

http://jacquelinelichtenberg.com