Linnea Sinclair and Susan Grant have fingered the exact problem most writers face. Most of us aren't criminals or megalomaniacs, not even deep inside. Most of us just want to make you laugh, smile, and cry all at the same time. We deal with the tender stuff inside our readers, not the coarse, gross, inelegant world outside.

After all we spend most of our young years reading (even in class, even when supposed to be doing homework, and sometimes even on dates!). We are readers more than we are do-ers, and as a result have a hard time thinking what nasty people would do.

Now we write fantasy (even SF is fantasizing of some sort, about the future, the galaxy, alternate times). And people don't read fantasy to get Headline News. (movies ript from the headlines, maybe, but not reading fantasy/sf/romance). We write classics to be enlightening a hundred or a thousand years from now, not a brief on current events.

So HOW DO YOU CRAFT A VILLAIN?

We don't know any villains. We see them on TV, read about them on Yahoo News, but they aren't in our social circles if they're "larger than life." They hold CNN Press Conferences. We just toil in our solitude hoping for a fan email from someone who has understood our novels.

Villains are complex and deep, so crafting them is especially difficult, as Linnea points out, when you're working in cross-genre with a severe word limit.

You can't include the whole life backstory of ALL the characters. Readers have to know what to infer from a few clues, so you have to craft a villain character readers (who like you don't know any villains) that the reader will instantly understand from a Japanese Brush Stroke image. Because your readers (and yourself) only see villains FROM OUTSIDE, you have to show your villain character from outside. There's no space to go that deep into them, and it wouldn't be fun for the reader.

If you want true-crime that goes into a psycho's head, you read something other than a romance spinoff genre.

So that's why we tend to create cardboard, cliche villains. Next week, I'll discuss how to accomplish this feat of larger than life character invention using Pluto as the ruling planet of Vampires and avoid the cardboard, single-dimenional villain problem. And in fact, I'll include last week's current events.

But right now, let's look at the easier part of the job of finding the antagonist/ villain/ Bad Dude.

So where do you look to find the correct villain for an SF Romance?

Back to the writing basics I keep harping on in these posts.

THEME. PROTAGONIST. PLOT. RESOLUTION.

That's where you find your villain/antagonist/BAD BUY.

The glue that holds the Romance plot and the Action plot together is THEME. Both plots have to be expressions of the same archetypal THEME, to say something about the same issue of morality, life, the universe and everything.

This structure saves you lots of words so you can put two genres together in the same wordage allowed for one genre. It's economics as well as art.

The theme comes from (or alternately generates; every writer and every project may randomly choose a different starting point -- but in the end, all the parts of the story must be in their proper places) -- so the THEME comes from the PROTAGONIST.

Look inside the protagonist, find what his/her life is really about (unbeknownst to him), then TEST TO DESTRUCTION that protagonist's view of life-the-universe-and-everything.

Find the one premise of that character's existence that he/she has never questioned, and present the protag with proof that the premise nearest and dearest to their heart is WRONG.

That's what antagonists do. Show the Protag how wrong he/she is.

The key to a hot romance is figuring out "what does he see in her" and "what does she see in him?" Both questions are answered by the THEME.

The key to a hot KILL THE ENEMY story is figuring out the tie between the two enemies. Why does this hero need THIS PARTICULAR VILLAIN? What inside the hero gives this villain a hook into the underside of his psyche?

Both the hot romance and the hot kill-the-enemy story need RELATIONSHIP DRIVEN PLOTS. They're just different relationships. (or maybe not so different)

WHAT DOES THE HERO NOT-KNOW ABOUT HIM/HERSELF? What does the hero keep secret from himself?

It is by that short-hair that the villain grabs hold of and jerks around the life of the hero and JOLTS the hero into becoming a Hero (Hero's Journey -- we all start as plain dudes and dudettes, and something happens that is NOT OUR FAULT and WHAM we are in a fight for our life against huge forces. And to win we have to solve that inner problem where those forces have hold of us.)

EXAMPLE: Guy photographs you in a compromising situation. Sends photo, demands money. He's got hold of you by your secret. What are you willing to do to protect that secret? The ONLY SOLUTION is to cease having the secret. So you plaster it all over the airwaves and the NYTimes -- you don't "confess" but you ADVERTISE as if it's a virtue not a shame.

When you reach the point where you're not ashamed of what you've done because it has brought you to a new psychological and spiritual level, there is no longer a place inside you where the villain can take hold. You are FREE. Problem solved.

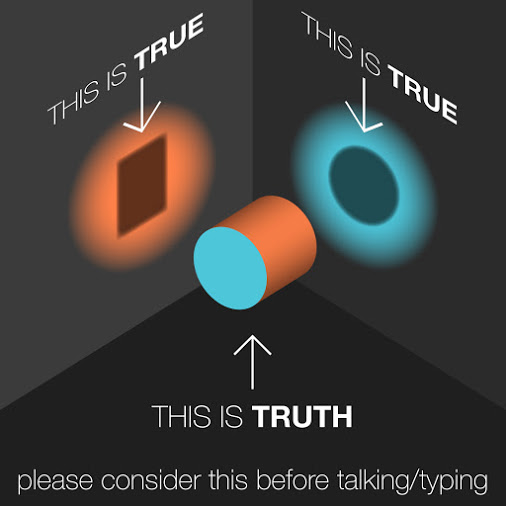

So to find the protagonist's natural antagonist, look deep inside the protagonist. The mirror image in the bottom of the protag's mind IS THE ANTAG.

This is where the amateur writer fails. This is where the "Mary Sue" story comes from. The failure of the author to LOOK INSIDE the protagonist because the protagonist is too much like the author, and so it's too painful to look too deep inside.

As Linnea points out, writing is the hardest work there is but she didn't mention that it's the least paid in money; hence the hunger for fan feedback -- not worshipful gaa-gaa fan feedback, but illustration that the work has propagated into others' lives as goodness.

Writing does drive some to drink because it does require that deep, inward searching and brutal self-honesty that other professions (not even psychiatry) do not require.

Now, sometimes you have to work the problem backwards. So think again about the story element list.

THEME. PROTAGONIST. PLOT. RESOLUTION.

Sometimes you have a protagonist and you know the problem, but what there is about the story that makes you want to write it is the RESOLUTION.

So to find the antag, look deep into the RESOLUTION. Dissect it. Analyze it. Find the philosophical core issue that changes because of the resolution. Lay back with your eyes closed, become the protag at the resolution moment and just FEEL the non-verbal effect you want to create for the reader in that end-moment.

I've been showing you in previous posts how to look at any issue using tools such as Tarot and Astrology to parse the real world down to its immutable (smallest indivisible unit -- just like the Greeks taught us) core components, then re-arrange the components in an original way and come up with a story element you can build on. The problem of generating the antag yields particularly well to these techniques.

Grab good hold of any ONE of these story components I've been discussing, any one, and ALL THE OTHERS ARE DETERMINED.

The art of story telling is just that -- understanding the relationship among things in this world and reflecting that relationship in the artistically created world.

In reality, your nemesis, your antagonist, actually lives inside you. Think back to High School. Who would you hide from? Would you hide from that person today? If your HS antagonist no longer lives inside you, you won't hide now.

Lots of good novels are about the moment of release when an adult vanquishes their HS antagonist forever -- by growing up themselves.

So if you have a protag, you already have the antag, plot, theme, resolution, etc etc. You even have the beginning, but that's the hardest to find. However, if you know the ending, then the beginning and middle are already determined.

In screenwriting, they call this relationship BEATS. I'm learning and practicing how to do that particular paradigm and having a ball at it.

This system works backwards too -- find the villain, look inside, and you'll find the protag who is that villain's nemesis.

The protag and antag are tied together along the axis of the theme. They are each living out different answers to the question posed by the theme.

Take the blackmail example again. The blackmailer has found that knowing someone's secret gives POWER. The blackmail victim has LOST POWER by losing the secret. It's all about the theme of the use and abuse of POWER. So every other backstory detail about both blackmailer and his/her motives and victim and his/her motives, right down to the breed of dog they own has already been DETERMINED by the nature of the thematic tie between Hero and Villain -- they have built LIVES based entirely on POWER, and probably have no room for LOVE.

Jacqueline Lichtenberg

http://www.slantedconcept.com