A blog post by fantasy author Seanan McGuire on what genre is and is not, plus her own expectations for genre:

Genre Is Not a PrisonFor one thing, it can be easier to tell what genre a particular work is not than what it is. McGuire cites one of the clearest examples, romance. Concluding with a Happily Ever After (or at least a Happily for Now) is essential to the definition of romance. Without that feature, a story isn't a romance regardless of any "romantic elements" it may include. GONE WITH THE WIND and ROMEO AND JULIET are not romances (in the modern sense, leaving aside the various medieval or Renaissance meanings of the term, which don't necessarily entail "love story" content). Her explanation reminded me of another component that used to be considered integral to the definition of "romance": Decades ago, a scholar of the genre defined a romance as the story of "the courtship of one or more heroines" (e.g., PRIDE AND PREJUDICE). The field has changed to make that definition obsolete; a romance novel today might focus on the love story of a male couple.

McGuire brings up the often-debated distinction between science fiction and fantasy, noting that people "can take their genres very seriously indeed" and that, for example, "Something that was perfectly acceptable when it was being read as Fantasy is rejected when it turns out to be secret Science Fiction." That potential reaction caused some disagreement between my husband and me, as well as with our editor, when the conclusion of the third novel in our Wild Sorceress trilogy revealed our fantasy world to have been an SF world all along. I worried that some readers might react with annoyance to what they might see as a bait-and-switch, and the adjustments we had to make to accommodate the editor's reservations validated my concerns. On the other hand, fiction with a fantasy "feel" that turns out to be SF isn't all that uncommon. The laran powers on Marion Zimmer Bradley's Darkover look like magic (and are viewed as such by the common people of that world), and a reader who starts with the Ages of Chaos novels might well be shocked when the Terrans arrive and Darkover is revealed as a lost Earth colony. The abilities of the characters in Andre Norton's Witch World series seem to be true magic, yet the stories take place on a distant planet rather than in an alternate world such as Narnia. And both authors' works are considered classics of the field, so those series' position on the fantasy/science fiction borderline hasn't hurt their enduring popularity.

I don't entirely agree with McGuire's comment about fantasy and horror: "Fantasy and Horror are very much 'sister genres,' separated more by mood than content." While true as far as it goes, this remark sounds as if all horror lurks under the same roof as fantasy. Granted, my own favorite subgenre of horror, which I encountered first and still think of as the real thing, is supernatural horror, a subset of fantasy—defined as requiring "an element of the fantastical, magic, or impossible creatures." As the Horror Writers Association maintains, however, horror is a mood rather than a genre. In addition to supernatural or fantastic horror in a contemporary setting, we can have high fantasy horror, historical supernatural horror, science-fiction horror (e.g., many of Lovecraft's stories), or psychological horror (e.g., Robert Bloch's PSYCHO).

McGuire does acknowledge the importance of mood in assigning genre labels: "Because some genres are separated by mood rather than strict rules, it can be hard to say where something should be properly classified." Does that mean we should give up on classifying fiction according to genre? Quite the opposite! I tend to get irked rather than admiring an author's bold individuality when he or she refuses to let one of his or her works (or entire literary output) be "typecast" as science fiction, horror, or whatever category the work clearly belongs to. McGuire seems to feel the same way: “'Genre-defying' is a label that people tend to use when they don’t want to pin themselves down to a set of expectations, and will often lead me to reject a book for something that’s more upfront about the reading experience it wants to offer me." Some authors seem to view the very idea of "expectations" with disdain, as if genre conventions inevitably equate to "cliche" or "formula." Do they feel equally dismissive toward the fourteen lines and fixed rhyme scheme of a sonnet?

As McGuire puts it, "And when someone wants something, they really want it. I react very poorly to a book whose twist is 'a-ha, you thought you were reading one thing, when really, you were reading something else entirely, whose rules were altogether different!' ” Genre, she says, at best resembles "a recipe. It tells the person who’s about to order a dish (or a narrative) roughly what they can expect from the broad strokes." Making it clear what ingredients the "dish" contains is one of the main jobs of marketing. Nowadays, a reader can discover works in exactly the niche he or she is looking for. On the Internet, a book needn't be shelved in only one category, and its genre components can be subcategorized as finely as the writer, publisher, or sales outlet chooses. So a fan of, to quote McGuire's example, “Christian vampire horror Western,” can find stories by like-minded authors.

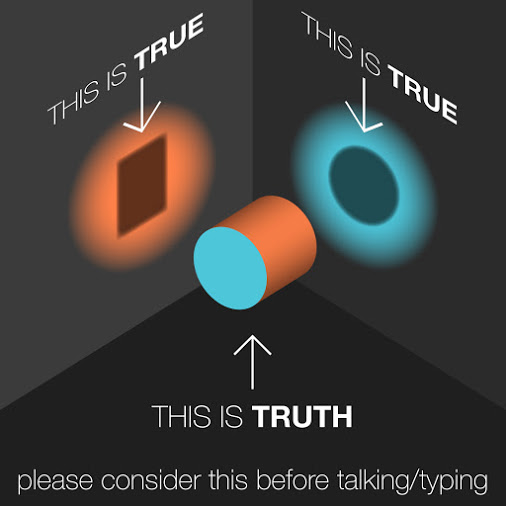

The concept of "fuzzy sets" can be useful in thinking about genre. A book that's an unmistakable, nearly archetypal example of fantasy would fall in the center of the "fantasy" circle. A different work that has many characteristics of fantasy but doesn't check all the typical boxes might belong somewhere between the center and the boundary of the circle. Some works feel like sort-of-fantasy but not completely and may include markers of other genres. They might fit into an overlapping zone between the "fantasy" circle and the "science fiction" or "horror" circle. A historical novel with a romantic subplot might appear at the intersection between historical fiction and romance. None of this hypothetical fuzziness, however, means that there's no such thing as genre or no point in categorizing fiction.

Margaret L. Carter

Carter's Crypt

No comments:

Post a Comment