I’ve been reading LIBRIOMANCER, by Jim C. Hines (who was one of the author special guests at MarsCon). In this novel’s version of our world, magic exists, unknown to the mundane population. Libriomancy, the kind of magic performed by the narrator, consists of the power to pull objects out of books as concrete items that function in the real world. The magic works with either fiction or nonfiction, so objects can be conjured from historical as well as imaginary settings. Characters seem fond of producing ray guns and other science-fictional weapons, but I find it more interesting when the narrator conjures such things as the shrinking and enlarging potion and cake from ALICE IN WONDERLAND, Peter Pan’s fairy dust, or Lucy’s healing cordial from the Narnia series. With this power, you’d think a libriomancer could do almost anything just by extracting objects from fantasy and science fiction settings. But the gift has restrictions, of course. A book serves as the physical portal between its setting and our world. Any object pulled through it has to be smaller than the book’s dimensions or at least capable of being folded that small. Also, the potential magic in a book depends on the emotional involvement, in a sense the belief, of its audience. Therefore, thousands of copies of the identical book must be in print and read before its story can be drawn upon by a libriomancer. That’s why it would do no good for somebody who wanted a time machine or a flying car to print up a twenty-foot-tall replica of the relevant novel. And some books have been magically “locked” because of the dangers inherent in some of their artifacts, such as the Bible and LORD OF THE RINGS. As for the objects withdrawn from books, normally the magician returns them to their source as soon as possible. Exceptions do happen. The narrator has a pet fire-spider, which he can’t restore to its book because it would burn the pages in the process. His girlfriend, a dryad, can’t have transferred directly from her novel into our world because of her size—but the acorn from which her original tree sprouted was brought into this world and accidentally allowed to remain and grow. About thirty species of vampires exist in this world as a result of different authors’ concepts of vampirism running amok; apparently a person who incautiously reaches into a book can be bitten and transformed by a vampire lurking therein.

I’m not clear whether a magician can take the same object from the same book more than once without returning it to its place first; various scenes offer hints, so maybe I’m just not interpreting them properly. Nor has the story mentioned whether more than one person can use different copies of the same book at the same time. The narrator does indicate that a particular copy of a book can be almost literally “burned out” by too frequent use. He also tells us that if a libriomancer overdoes the magic, voices from the books start to creep into his head. Extreme overuse of the power can lead to possession by fictional characters.

Regardless of the restrictions, I think this would be a fun power to have. I wouldn’t mind having a love potion, for example, not for unethical mind control but for sharing between already mated lovers just for fun. A tribble would fit through the boundaries of a book and would make a delightful pet if one took care not to overfeed it. I’ve read stories that include magical desserts with all the taste but none of the calorie-dense substance of the real thing, a treat I would definitely enjoy. To me, such uses of the magic would be more interesting than the production of futuristic weapons, which amount to nothing but bigger, badder versions of items we already have. It’s safer, too, to stick to modest desires. Imagine if somebody evoked Aladdin’s wishing lamp and it fell into the wrong hands. (According to the narrator, that wouldn’t work anyway, because the transition from fiction to reality would drive the genie insane.) Magical ambitions to make major changes in the world or even one’s own life seldom end well.

Still more attractive to me, though, would be the power to get inside books, as the children in one of Edward Eager’s novels do; for instance, they visit the setting of LITTLE WOMEN and go ice skating with Meg and Jo. I’d rather take a vacation in Narnia or the Shire than bring hazardous magical artifacts into my home environment. Or I could meet one of the romantic “good guy vampires” I love reading about. Of course, one would have to be careful while choosing scenes to jump into and have a foolproof way of getting out whenever danger looms. The heroes of the classic fantasy novel THE INCOMPLETE ENCHANTER get into plenty of trouble in the worlds of Norse mythology and Spenser's FAERIE QUEENE. There’s a short story called “I Shall Not Leave England Now” with an enchanted cabinet that allows anyone to enter the scene on the page to which a book in the cabinet is left open. A careless user leaps into Stoker’s DRACULA and lands in the wrong scene, the night when Dracula comes ashore in Whitby. Upon emerging from the book, the character has been bitten and transformed into a vampire.

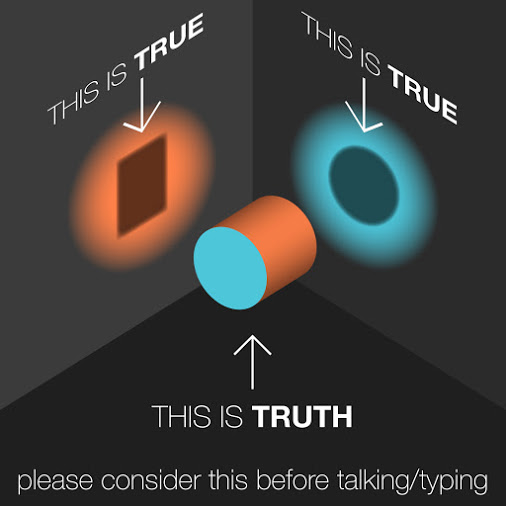

In short, as we’re often told in the TV series ONCE UPON A TIME, magic always comes with a price. Or so it usually works in an effective story.

Margaret L. Carter

Carter's Crypt

Having finished reading LIBRIOMANCER, I've discovered that the rules do allow taking the same object from the same book more than once. The magician has to wait for the item to "re-form." However, as mentioned, the use of a single copy of a book isn't infinite, because it gets a little more "charred" each time and eventually burns out.

ReplyDelete